Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are a problem. There are approximately 100,000 ACL tears in the USA each year at a financial cost of $1.7 billion.

Most injuries are sport specific, however, non-contact ACL injuries seem to follow a more gender-specific trend. Female athletes sustain ACL injuries 2 to 8 times more frequently than male athletes!

The high risk group for these ACL injuries is females between the ages of 14 and 20 years and 70% of ACL injuries occur in non-contact situations. The sports where the incidence of ACL injuries is the highest are sports such as soccer, volleyball and basketball that require pivoting, cutting and rapid deceleration.

In 1972 a USA amendment, Title IX, was passed that enabled women to participate in athletic events without gender or financial discrimination. This legislation not only resulted in a 6-fold increase in female sports participation to over 3 million in 2004 with soccer the number 1 female sport at collegiate level, but it also resulted in a large increase in the number of sport related injury, including non-contact ACL injuries.

With this dramatic increase in ACL injury the sports medicine community wanted to determine why females are more prone to ACL injuries than their male counterparts. Studies looked at a variety of aspects to try to identify the main factors that lead to an increased risk of ACL injury in females. The four areas that have been associated with increased risk of ACL injury in the female athlete are anatomy, hormones, environment and biomechanics. The size and shape of the ACL, the intercondylar notch and the pelvis; ligament laxity; body mass index (BMI); and hormonal variations have all been evaluated as potential factors for ACL injury. Despite some excellent studies looking at risk factors for ACL injury no single environmental, anatomic or hormonal factor has been shown to be responsible for the increased risk of ACL injury in female athletes.

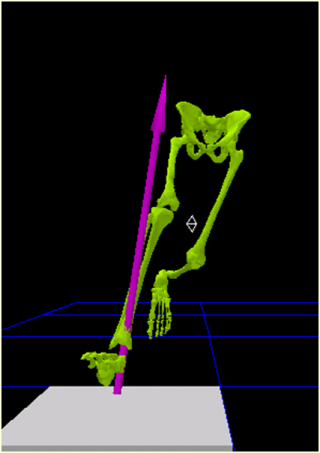

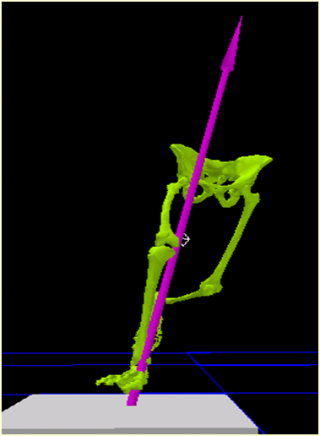

Research efforts have now switched to looking at whether biomechanical and neuromuscular factors directly contribute to ACL tears. Women typically run more erect than men and have decreased knee and hip flexion. In addition, women activate their hamstring muscles more slowly than males when decelerating. This is very important when the role of the ACL is considered. The ACL is important in stabilizing the knee joint by preventing forward movement of the tibia (shin bone) in relation to the femur (thigh bone). The combination of decreased knee flexion and slower hamstring activation result in the ACL being put under increased stress in females compared to males especially when landing from a jump or decelerating.

Here at Santa Monica

Here at Santa Monica