Factors increasing the Q-angle

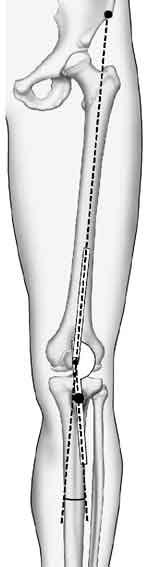

I'm moving on to the third group of conditions which can affect the mechanics of the knee - 'factors affecting the q-angle'. Before we get there, do you want to have another quick look at that q-angle picture we discussed in the Part II? It is an important concept.

The Q-angle is the angle formed between two lines -

- from the prominent bump on the pelvis bone above the hip through the centre of the patella

- from the prominent bump on the tibia (tibial tubercle) through the centre of the patella

[Reprinted with permission, The Adult Knee, Chapters 59-60, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.]

It gives an idea of the angulation of femur bone to tibial tubercle, and the consequent stresses which may be contributing to bowstringing - i.e. pulling the patella to the outer (lateral) side of its groove.

I want to stress that it is the tibial tubercle, not the tibia bone itself, which forms the lower reference point. The tibial alignment can be relatively normal but the q-angle increased if the tibial tubercle is displaced too far to the side.

The existence of the Q angle (see Anatomy in Part I) causes the patella to move laterally when a person tightens their thigh muscles. When the Q angle is elevated, the patella has a greater tendency to move laterally. This can contribute to a painful patella and/or lead to an unstable patella, where the patella slips out of its groove. The following conditions affect the Q angle -

- Flat feet - The collapse of the foot's arch leads to twisting of the tibia, femur and extensor mechanism when the person takes a step.

- Lateral positioning of the tibial tuberosity - The main determinant of the Q angle is the position of the tibial tuberosity. If the tibial tuberosity is laterally positioned (too far to the right on a right knee), the Q angle by definition will be increased.

- Valgus - A knock-kneed position moves the tibial tuberosity laterally.

- Tibial rotation ('miserable malalignment') - 'Miserable malalignment' is the colloquial name given to 'complex torsional variations' (abnormal femoral and/or tibial rotation) in limb alignment from the hip down to the ankle.

When the patient is examined standing the knee cap can point inwards ('squinting') or outwards ('grasshopper patella'). The hip joint is usually excessively turned out, the end of the thigh bone can twist inwards or outwards, the upper tibia is commonly twisted outwards, the tibia displays a bow-legged appearance, and finally even the ankle can be twisted outwards. And when all is said and done, one twist compensates for another from the hip all the way down to the foot until the foot points forward!

When the patient is examined standing the knee cap can point inwards ('squinting') or outwards ('grasshopper patella'). The hip joint is usually excessively turned out, the end of the thigh bone can twist inwards or outwards, the upper tibia is commonly twisted outwards, the tibia displays a bow-legged appearance, and finally even the ankle can be twisted outwards. And when all is said and done, one twist compensates for another from the hip all the way down to the foot until the foot points forward!

[Reprinted with permission, The Adult Knee, Chapters 59-60, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.]

Such anatomy can be associated with pain at the front of the knee . Clearly, the knee cap is an innocent bystander in this complex malalignment. Imaging will often reveal a normally-positioned knee cap overlying a rotated femur. Fortunately, pain can often be controlled with activity modification, stretching and strengthening exercises. For the patient requiring surgery, so-called small procedures such as a lateral retinacular release are not usually successful. On the other hand, the untwisting bone cutting procedures (osteotomy) are substantial, and there are no long-term reports of their results.

Now, I am aware that you have had to take in a lot so far with this lesson on 'differential diagnosis'. The end of this page is quite a good place to take a break if you would like that.

I'll just round up about 'malalignment' which we have already mentioned several times.

Outside of overuse and simple tendinitis, malalignment is arguably the greatest source of persistent knee pain in patients between the ages of 20 and 50.

Patella malalignment is a translational or rotational deviation of the patella relative to any axis. This includes a knee cap that sits too high or too low in the trochlea, as well as an elevated Q angle, patellar tilt and 'miserable malalignment'.

You should know that the very existence of patella malalignment as a clinical entity remains a subject of dispute within the orthopaedic world. Otherwise knowledgeable health professionals state that tilted knee caps are normal, and they base that argument on the fact that they often see tilted knee caps that are painless.

It is my feeling that they are confusing the term normal in the everyday sense with the term normal as it might be used in the world of medicine. 'Normal' in everyday day language means common or acceptable. In that sense, it is indeed 'normal' for a segment of the population to develop cancer or heart disease. But a medically normal condition is one that does not lead to death, disease or pain, and in that sense of the word, cancer and heart disease are clearly not normal. Kneecap malalignment is normal in the 'common' sense of the word, but not in the medical sense. An analogy here can be made with flat feet: they are common, they are not necessarily painful, but they are not normal.

Patellar malalignment appears to be related to a number of factors that appear in varying degrees. These include constitutional laxity (being loose-jointed), paradoxical tightness of the ilio-tibial band and of the lateral retinaculum (these are tight while every other joint is loose!), abnormal positioning and contractions of the VMO muscle, anatomic variations of the trochlea, a high riding knee cap, and a tibial tuberosity that is too far off to the outside (elevated Q angle).

The pain is presumed to result from excessive pressure on part of the knee cap (right side of a right knee cap, the left side of a left knee cap). However tilt itself does not completely account for the onset of pain as evidenced by the observation that not every patient with malalignment is symptomatic. Pain appears to be related to multiple other factors that have yet to be identified.

Blunt trauma to the front of the knee and overuse are two of the many potential triggering mechanisms. Nerve abnormalities have been noted in the lateral retinaculum, but it is not clear whether these are always present. As with tightness of the lateral retinaculum, it is also unclear whether the nerve abnormalities are the cause or the result of the condition.

When the patient is examined standing the knee cap can point inwards ('squinting') or outwards ('grasshopper

When the patient is examined standing the knee cap can point inwards ('squinting') or outwards ('grasshopper